- Home

- Height

- Length

- Style

- Theme

- Abstract (5)

- Animal (7)

- Animal Hunting (14)

- Animal-themed (17)

- Animals (60)

- Bust (5)

- Character (108)

- Collectible (4)

- Couple (5)

- Dancer (14)

- Fashion (6)

- Flower, Tree (4)

- Genre Scene (30)

- Graffiti (5)

- Landscape (18)

- Mythology, Religion (6)

- Nudes (4)

- Seascape, Boat (9)

- Sexy (5)

- Still Life (8)

- Other (3291)

- Type

- Acrylique (23)

- Applique (26)

- Coupe à Fruits (52)

- Dessin (65)

- Drawing (23)

- Figurine, Statue (126)

- Gouache (23)

- Gravure (29)

- Huile (135)

- Lampe De Table (74)

- Lampe Tulipe (25)

- Lithographie (35)

- Oil (72)

- Plafonnier (26)

- Sculpture (357)

- Statue (159)

- Statue Sculpture (236)

- Statue, Sculpture (169)

- Suspension, Lustre (116)

- Vase (98)

- Other (1756)

- Width

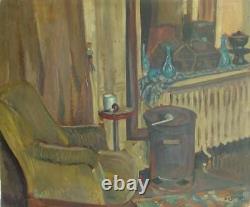

Jean DORVILLE (1902-1985) HsP 46x55cm 1945 School of Paris Art Deco Nabi Fauvism

Signed and dated in the lower right corner. Very Beautiful Oil on board. Handsigned and dated on lower right. 18.1" x 21.6" in. National School of Decorative Arts of Paris.

Exhibited at the Salon d'Automne and at the Salon des Indépendants. Retrospective at the Paris City Hall in 1954. This interior with the suede armchair and charcoal stove invites us to the peaceful warmth of the opulent homes of the 40s.

All is sweetness, charm, and refinement. Art Deco is an artistic movement that emerged in the 1910s, reaching its full bloom in the 1920s before declining in the 1930s.

It was extremely vibrant, especially in the decorative arts, architecture, design, fashion, and costume, but it actually influenced more or less all forms of visual arts. It is the first style to have achieved global diffusion, primarily affecting France, Belgium, all Anglo-Saxon countries (United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, Philippines, etc.), as well as several Chinese cities like Shanghai and Hong Kong. The Art Deco style takes its name from the International Exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925.

The vocabulary varies in form depending on regions, architects, and their clients, but its stylistic unity relies on the use of geometry (and geometricization) for decorative purposes. Without a true leader or theory, this style was criticized from its early years for its superficiality. It was particularly used for buildings meant to enhance the image of their patrons or evoke leisure: commercial architecture, headquarters, etc., theaters and cinemas, but also domestic architecture (the decor serving as a sign of social distinction). Initially affecting the wealthiest classes, it quickly spread throughout the social body and became very popular.

A reaction against Art Nouveau emerged as early as the beginning of the century in France, and even earlier abroad, such as in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, etc. Some already describe Art Nouveau forms as "soft" or "noodle style" (nou). They then turned towards simple lines, classical compositions, and a sparing use of decor.

This desire for a return to order, symmetry, and sobriety took different expressions depending on the countries. In Austria, for example, the undulating line of the early Art Nouveau period was quickly replaced by a network of orthogonal lines and simple volumes under the influence of Scottish architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, Otto Wagner, and the Wiener Werkstätte are the emblematic artists of this trend. The interiors, known through photographs, mobilized the entire Wiener Werkstätte and painter Gustav Klimt. In France, the first signs of this desire for change were noticeable as early as the 1900s.

In 1907, Eugène Grasset published a Method of Ornamental Composition that favored geometric forms and their variations, contrasting sharply with the undulating freedom of the Guimard style, which had been so popular in Paris a few years earlier. The following year, Paul Iribe designed a fashion album for Paul Poiret, whose aesthetics struck the Parisian milieu with its novelty. A third significant event, the Salon d'Automne of 1910, saw the invitation of Munich artists who had adopted strict forms for several years. Around 1910, French decorators André Mare and Louis Süe also evolved their style towards greater rigor and restraint.

Finally, between 1910 and 1913, the construction of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées took place, another sign of the radical aesthetic change happening in Paris at that time. Initially entrusted to Henry Van de Velde, the design and construction quickly reverted to Auguste Perret. The rigorous composition of the façade and the measured space left for decor struck the minds during its inauguration in 1913. These evolutions were summarized in 1912 by André Vera. His article "Le Nouveau style," published in the journal L'Art décoratif, expressed a rejection of Art Nouveau forms (asymmetrical, polychromatic, picturesque, which excite feelings more than reason) and called for "voluntary simplicity," a "unique material," and "manifest symmetry." The end of the article urges artists to draw inspiration from the classicism of the 17th century marked by "clarity, order, and harmony" and to resume the thread of the history of French styles from the Louis-Philippe period, without pastiche. Vera's final words describe two themes that will be omnipresent in the future Art Deco style: "the basket and the garland of flowers and fruits." The influence of painting should not be overlooked in explaining these evolutions. The 1910s were a time of diffusion and popularization of Fauvism and even more so of Cubism.

The painters of the Section d'or exhibited works that were often more accessible to the public than those of Picasso and Braque during the period of analytical cubism. Themes of sports, workers, etc., and vibrant colors contrasted with the fragmented and avant-garde still lifes of the movement's pioneers.

The cubist vocabulary was ripe to attract fashion, furniture, and interior decoration creators. Finally, Paris in the 1910s discovered Serge Diaghilev's Russian ballets, blending dance, music, and painting, inspired by "One Thousand and One Nights," offering an invitation to luxury and exoticism; the costumes were created by Léon Bakst and many others. Hence the fashion for fans, feathers, water jets, and bright colors.

Unusual colors would impose themselves in decor and furniture: we would see boudoirs with orange walls, salons upholstered in black. Order, color, and geometry: the essence of the Art Deco vocabulary is established. The Roaring Twenties World War I profoundly wounded the economies and societies of France and Germany. While Germany in the 1920s was crushed by the blows of defeat and a severe economic crisis (as evidenced by the artists of the New Objectivity), France saw its economy recover. This recovery did not erase the difficulties on the ground. The destroyed cities needed to be rebuilt (such as Reims and Saint-Quentin, for example, which were 80% destroyed during the war and would be largely rebuilt in an Art Deco architectural style). Additionally, monetary instability generated a constant rise in prices until 1927, and rent legislation caused a severe housing crisis for the working and middle classes. However, the early 1920s also saw manifestations of the intact fortune of the wealthiest classes. In Paris, as in major provincial cities, contemporary commentators observed the construction of wealthy apartment buildings, villas, and mansions. All of these were prolific construction sites for decorative artists and Art Deco architects.